The Shape of a Room: A Gentle Reckoning.

Coffee in hand, I opened one of my favourite books, Axel Vervoordt’s Wabi Interiors. Have you heard the expression Wabi Sabi? A Japanese aesthetic and worldview. It values what is imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. The phrase joins two roots:

First used in poetry, wabi referred to loneliness or poverty; it later came to describe a simple, humble beauty. Under the influence of Zen Buddhism, with its sensibilities around solitude, imperfection and simplicity, wabi shifted away from suffering toward intentional simplicity.

Sabi first meant something like withered, worn, chill – a sense of desolation and again under influence of Zen Buddhism, evolved into an aesthetic of quietness, patina, and the dignity of age.

Together, wabi-sabi is a way of seeing. A cracked tea bowl repaired with gold (kintsugi) is wabi-sabi. Moss on an old stone wall. A linen cloth frayed at the edge. Rooms that breathe, objects and materials placed with presence rather than for show, materials that show their life. In Wabi Inspirations, Vervoordt is speaking specifically of wabi – the simplicity and presence – rather than the fuller concept of wabi-sabi.

A room that breathes. A beloved bowl with a chip. Light falling in the late afternoon on linen. I was sitting with the book, looking at pictures of a house once owned by Picasso and later touched by Vervoordt. The patina on the doorframe. A door left ajar that only the right light knows how to enter. Every object placed as if it remembers something, as if it chose to be there.

Earlier this year, I spent time with a teacher, more conduit than coach, who gave words to what I’d always felt: objects choose their place. The words felt like recognition. What matters are the relationships in the room, not the decor. The lamp and the window, the chair and the wall, the mug and the morning. Even the silence seems to have direction. The spaces feel alive. There’s nothing performative about them, and what a relief that is.

Like a forest. Grounded presence. Permission. Spaces you walk into and know exactly where to sit, because the room already knew.

I find spaces like that reassuring, probably because I can get a bit cluttered and love it when a room is spacious and intentional, with objects and natural forms that embody or remember their nature. A stone, a hand formed vessel, a wooden bowl that still smells like the tree it came from. Bringing the outside in, or taking us from inside to out. It’s not about being tidy or minimalist, but attunement. And when a space holds attunement, much like when a person holds attunement, something inside can settle.

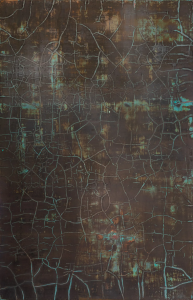

I was minded of the work by Andrew Szczech. The crackle as memory, colour emerging from within, like minerals rising through stone or breath warming metal. Each piece feels touched by time and left to cure, inviting you to enter – like the Axel rooms.

And then I recalled a conversation between Anselm Kiefer and Tim Marlow, (which I referenced in a piece I wrote for MoneyWeek.) Kiefer in his vast warehouse of memory: ash, lead, straw, myth. Diamonds cast into dark soil, canvases flooded with molten lead. Even now, it sounds like scripture – of matter. Kiefer does not paint images; he builds memory into mass, pressing history into surface.

Andrew’s work feels more distilled. Less myth, more mineral. Still, they share something: a reverence for what is buried, perhaps, or a willingness to stay close to the crack. Both concerned with time, material, memory. There’s weight in them. Gravity. They stand like ruins, or offerings. Structures of invocation. You don’t view them; so much as stand before them.

Yes, Kiefer constructs altars to grief, to myth, to the scorched trace of what was. And Szczech – it seems to me is an architect of pause, the pause after collapse. That cracked surface is not a gentle patina, it’s scar tissue. Still beautiful, but not neutral. The reference to broken utopias, surface as both wounded and worshipped, a deliberate, layered re-encoding of power, violence, loss. A reckoning.

Held softly, with precision. There is weight, but also wear. A kind of eroded elegance. You feel the passing of time as surface: abrasion, sediment. And yet, somehow, it is still, emergent – revealing itself like old wallpaper coming through new paint. Slow. Grounded. Intentional. Meditative.

There is a quiet urgency in Andrew Szczech’s work that feels aligned with this moment. It is reckoning, held in surface, in silence, in the shape of a room.

Alongside Andrew Szczech, I’ve gathered a group of works that resonate with this reflection.